The five Dhyani Buddhas are transcendental enlightened beings (Buddhas) as compared to their earthly, human counterparts known as Manusa Buddhas. Each of the Dhyani Buddhas is linked with a specific cosmic time cycle, and also with a "family" of beings and attributes. The five-fold division of the cosmos in line with the Dhyani Buddhas recalls the Wuxing classification in China, but we will not pursue that lead in this article.

Dhyani Buddhas are particularly associated with the five primary colors -- white, blue, red, gold/yellow, and green.

In Islamic mystic tradition, the Five of the Mantle (or Cloak) -- Muhammad; his daughter Fatima, her husband 'Ali; and the couple's sons al-Hasan and al-Husayn -- become primordial, transcendental beings in Twelver Shi'ism. They are said to have existed before Creation and are linked with successive cosmic cycles in a manner remarkably similar to that of the Dhyani Buddhas. Additionally, the five are associated with the "Five Lights" or "Five Colors" a reference to the human incarnations of these transcendental beings.

In Tibetan Buddhism, the five Dhyani Buddhas are combined with a sixth being -- the Adibuddha -- representing the pantheistic totality of the group. Similarly in Islamic mystical tradition, the angel Gabriel becomes the "sixth of you five," which Henry Corbin describes as the "uni-totality" of the pentad. In both the Tibetan and Islamic systems, this sixth member is associated with the element of the mind, as Vajrasattva (manas "mind") in the case of the Adibuddha, and as the Ruh Natiqa or "Thinking Spirit" in the Ismaili tradition.

Body of Light

The association of the Dhyani Buddhas and the Five of the Mantle with the five colors links conceptually with the belief found in both schools that spiritual adepts can attain a "body of light."

In the Dzogchen and Bonpo traditions of Tibet, this is known as the Rainbow Body or the Rainbow Light Body. Upon the attainment of the highest yogic plane before death, the yogi dissolves into the "Five Pure Lights," i.e., the five primary colors of the rainbow achieving union with the Dharmakaya, the pantheistic godstuff.

The Sufi "body of light" or "resurrection body" is attained by the adept who completes a sacred itinerary that is generally thought of as imaginal in nature. Actually the final part of the journey is that in which the devotee travels to union with the Divine in this subtle body of light.

The Inner and Outer Journey

Both the Tibetan and Islamic mystical traditions include concepts of a pilgrimage that the adept undertakes to attain spiritual transformation.

In the Tibetan case, there are clearly both real world along with imaginal sides to this tradition. The pilgrimage sites are real places that have been traditionally used as such including Kamarupa in Assam, the Gondavari River in South India, and the Himalayan range in Nepal and Tibet. The only really exotic destination is Suvarnadvipa, which also happens to be a key location in this blog's research.

The Tibetan pilgrimage sites are divided into five major groups -- the pitthas, ksetras, chandohas, melapakas and smasanas -- and these are further subdivided by adding the prefix upa- to each major group. Thus there are five groups of pilgrimage sites, ten in all including subgroups, that are said to correspond also to ten parts of the human body:

Suvarnadvipa is included in the group known as the upamelapakas, which are associated with the feet and the calves. According to Jamgon Kongtrul, the inner journey of transformation begins interestingly enough from the head and then moves downward toward the feet. Suvarnadvipa is found at the eighth stage of awakening and is associated with the sacred ground known as the "Higher Gathering Place." The sacred grounds of the ninth and tenth stages are known respectively as "Cemetery" and "Higher Cemetery" suggesting that the adept is already passed on beyond this life.

The Sufi and Shi'a sacred journey is represented by the journey of the birds to the East toward Mt. Qaf, the eighth mountain in a system that consists of either nine or ten stages. The birds never proceed beyond Qaf, which is known as the Footstool of God, for the next stages take the adept to the very Throne of God.

For the Sufi mystics also, the inner itinerary begins from the top, starting in the eyes according to al-Kubra then moving down into the face, the chest, and then the rest of the body. Like Suvarnadvipa, the eighth stage of the Tantric pilgrimage, Mt. Qaf, the eighth sphere, was located in the furthest East. Abassid tradition places it "behind," i.e. on the other side of the China Sea.

Kabbalah echoes

The Zohar, the central text of Kabbalah that dates back to 13th century Spain, also emphasizes a journey, mainly spiritual in nature, that the practitioner undertakes to reach Gan Eden -- the Garden of Eden, also known as Pardes. There are actually two Garden of Edens -- a heavenly one that one attains to after death, and an earthly garden where the Shekinah is exiled.

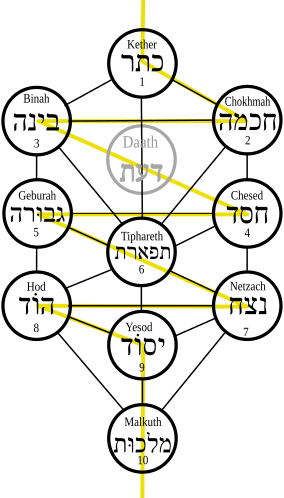

The Shekinah is the female aspect of the Divine that remained in the Terrestrial Paradise after the banishment of humanity. The Kabbalah adepts seek to rejoin the Shekinah via a sacred pilgrimage to the primordial garden through mystical paths known as Sephirot. The Sephirot were likened to the organs of the human body, specifically that of Adam Kadmon, the Primordial Man.

The Sephirot shown in a traditional diagram. (Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tree_of_life_hebrew.svg)

From Wikipedia: "Metaphorical representation of the Five Worlds, with the 10 Sephirot radiating in each, as successively smaller Iggulim-concentric circles."

At the top of the body is the first Sephira, Keter, the crown of the head, while the tenth and last Sephira corresponding to Gan Eden is Malkuth, which also represents the feet of Adam Kadmon. The Hebrew term malkuth is related to the malakut of Islamic mysticism with both words referring to the "realm of kings," an area on the border of the earthly and heavenly regions.

Although the sacred journey of Kabbalah was an inner one, the belief in a real world Gan Eden did exist. According to medieval documents like the Hebrew letters of Prester John, the location of Gan Eden was 'India ha-gedolah or "Further India," the same area where one finds the Sambatyon River and the Lost Ten Tribes of Israel.

Evidence exists that at least some medieval Kabbalists undertook real journeys to these far-off locations. For example, Abraham Abulafia attempted to find the Sambatyon River with the idea that he could help the world along toward the end times, but also to help undo the "knots" that hindered his own spiritual development.

Echoes in the East

Suvarnadvipa (Island of Gold) in the Tibetan version of the spiritual itinerary would equate with the locations of Qaf and Gan Eden in the respective Islamic and Kabbalah traditions. As I have argued often here, the Ming Dynasty kingdom known as Lusung (Luzon) was the political and cultural heir to Suvarnadvipa and located in the same geographical political center.

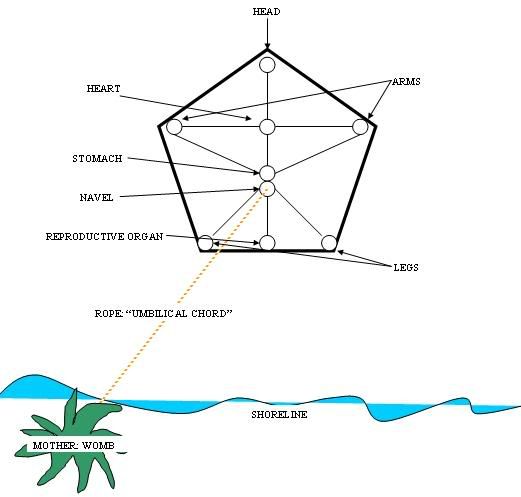

Here we can still find the concept of cyclic and generational time represented in the image of a human body divided into five parts. The body thus divided could represent five generations of a clan, and also the cycles of regeneration and reincarnation that existed in the previous belief systems.

I have also suggested previously that the sacred lands of Lusung were apparently divided in a quadripartite fashion based on the imagery of the human body. Thus, we have place names like Olongapo or Ulo ng Apo "Head of the Lord."

Another example of the human form representing the cosmos or at least the Earth can be seen in the Tausug house architecture that interlinks Earth, tree, house and human body.

A diagram of a traditional pentagonal Tausug house made with nine posts that create an outline of a human body in the well-known squatting figure motif. The tree acts as the umbilical cord of the Mother Earth extended by a rope tied to a central post. After nine months, the period of human gestation, the rope is cut. (Sources http://media.photobucket.com/image/tausug%20nine%20square%20house%20numbers/kharl_prado/tausug.jpg)

The house with it's symbolic human figure represents the "child" of the Earth and thus is a copy of the world in microcosm. While the oldest form of the Austronesian house had four corner posts, a central post is often added symbolically to represent the center of the world. Thus, the five posts create an imagery of the cosmos. In the Austronesian scheme of the base, trunk and tip, the base of the house is the bottom and thus one travels back to the "source" by going from top to bottom.

In another sense, the mythical family of Pinatubo and Arayat can be compared to the Holy Family of the Mantle in Islamic tradition. In the local folk legends, this family is often represented with five members, for example, Sinukuan and his spouse and their three daughters. However, an extensive review of the traditions would allow us to logically reconstruct the family as consisting of the two deities of Pinatubo and Arayat, standing for the Moon and Sun respectively; a single child for each of these deities, more connected with the Earth, who are involved in a battle-courtship; and the offspring of the latter who again has an astronomical relationship representing Venus, the Morning Star.

Islamic mystical tradition normally equates Muhammad with the Sun; 'Ali with the Moon; Fatima with Venus; while the al-Hasan and al-Husayn are sometimes equated with the pole stars. The emphasis on the luminaries and Venus to the exclusion of the other planets is quite telling. The astronomical links here are clearly associated with the association of these "families" with cyclic time.

We also hear of widespread beliefs surrounding the rainbow in the Philippine region . In some cases, the rainbow was equated with the Supreme Deity, while elsewhere it is seen as the abode of God or the gods. Sometimes it is viewed as a bridge or boat by which one reaches the Divine after death. There was a belief that people who died a noble death by the sword, or who were devoured by crocodiles, or struck by lightning, became anitos (deified spirits) and were united with the pantheistic Deity in the rainbow, or through the vehicle of the rainbow.

In Pampanga, the pantheistic nature of the rainbow can be seen in its name pinanari "loincloth of the King" with the "king" here probably referring to the creative force Mangetchay.

Concepts of transformation are also included in the practice of obtaining a mutya, although in this case the transformation involves those still living on earth. Mutya refers to a pearl or gem that shines and radiates light. Grace Odal-Devora states: "...the inherent powers and virtues of the various mutya objects can be the basis for conceptualizing on the nature of the self – that starts from discovering the innate powers and inherent virtues within and using them to transform oneself and one’s society – like the transformation of the pearl from slime, mud, sand or dirt into a gem of light, beauty, healing and purity."

Regards,

Paul Kekai Manansala

Sacramento

References

Cooper, David A. The Ecstatic Kabbalah. Boulder, Colo: Sounds True, 2005.

Corbin, Henry. Cyclical time and Ismaili Gnosis, http://www.amiscorbin.com/textes/anglais/Corbin%20Cyclical%20Time.pdf.

Idel, Moshe. Studies in Ecstatic Kabbalah. SUNY series in Judaica. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1988.

Karma-gliṅ-pa, and W. Y. Evans-Wentz. The Tibetan Book of the Dead: Or, The After-Death Experiences on the Bardo Plane, According to Lāma Kazi Dawa-Samdup's English Rendering. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Katz, Nathan. Indo-Judaic Studies in the Twenty-First Century: A View from the Margin. New York: Palgrave Mac Millan, 2007, 64-5.

Merkur, Daniel. Gnosis: an esoteric tradition of mystical visions and unions. SUNY series in Western esoteric traditions. Albany, NY: State Univ. of New York Press, 1993, 217-245.

Odal-Devora, Grace. 2006. Some problems in determining the origin of the Philippine word "mutya" or "mutia." Paper presented at Tenth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics. 1720 January 2006. Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines. http://www.sil.org/asia/philippines/ical/papers.html.

Reyes y Florentino, Isabelo de los. Notes in order to familiarize myself with Philippine theodicy : the religion of the Katipunan which is the religion of the ancient Filipinos, National Historical Institute, 1980, 4, 6.

Sakili, Abraham P. Space and Identity: Expressions in the Culture, Arts and Society of the Muslims in the Philippines. Diliman, Quezon City: Asian Center, University of the Philippines, 2003.

Silliman, Robert Benton. Religious Beliefs and Life at the Beginning of the Spanish Regime in the Philippines: Readings. Dumaguete City, Philippines: Reproduced by College of Theology, Silliman University, 1964.

Wallace, Vesna A. The Inner Kālacakratantra A Buddhist Tantric View of the Individual. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Zangpo, Ngawang, and Blo-gros-mtha'-yas

![[14jul'09,totem+poles.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEipSR4zzo2w0eCwaAxbTd7KK8JaciH_sXb-z5_L0q9G4Hh0eBgu_3PbSwYm77YPRBj6Wy-kcWEO0M7CjzDaHOkVn8uO1fCJ0TThoCXnxxYTBsHxfMF8bigUoNSgb_UdPD65bex9Xw/s640/14jul'09,totem%2Bpoles.jpg)