Japanese linguists have for decades uncovered significant Austronesian influence, mostly interpreted as specifically Malayo-Polynesian influence, in the Japanese language. If we accept Solheim's views that the transfer of Yayoi culture to Japan was a gradual process that took several thousands of years, we must wonder if Japanese mythology and legendary history conveys any information on the Nusantao past.

The "other worlds" of Japanese mythology often double as foreign countries in Japanese literature. The most important were known as Takamagahara "Plain of the High Heaven," Nenokuni (also Yominokuni) "Root Country (or 'Motherland') and Tokoyonokuni "Eternal Land."

Since the Meiji Era, Japanese scholars have attempted to connect these fairylands with known foreign geography.

All these locations are associated with the ocean and long sea voyages in the direction of the South. Furthermore in Okinawa and the Ryukyus, these lands are known by names like Niraikanai, Nirai, Nira, Niza, etc. depending on the location. Again, the semi-mythical locations are said placed in the ocean requiring a long journey and tend to be located toward the South.

In Japan, the southernmost tip of Kyushu, the lands associated with the ancient Kumaso and Hayato tribes were the traditional departure point and port of entry for journeys to and from the "other worlds."

Japanese scholars have sought locations for these lands from Melanesia to South China, Taiwan, Tibet and Korea.

Plain of High Heaven

Takamagahara is the sacred land from where Ninigi, the ancestor of Emperor Jimmu, came to land in southern Kyushu.

Ninigi is connected with the southern Kumaso and Hayato peoples, despite the fact that the Yamato Dynasty later has trouble pacifying their southern lands. One of Ninigi's sons is described as the ancestor of the Hayato people of southern Kyushu.

The Kumaso tribe was closely related to the Hayato or "Falcon People" and appear to have preceded Ninigi in Kyushu. Legend states that the Kumaso came to Kyushu on the Kuroshio or "Black Current" (Japan Current). They are described as having tattoed bodies, shields decorated with hair and bamboo hats.

Ninigi, like the visitors or Marebito from Niraikanai to the Ryukyus, was associated closely with rice agriculture, believed from the archaeological standpoint to have been brought by the Yayoi people. According to Japanese tradition at least, it was not until the day of the Empress Jingo and her expedition to Korea in 200 CE, that imperial influences begin to flow from that country and also from China, either directly to Japan or through Korea.

One might connect the earliest indigenous state culture in Japan with the Kofun burial mounds, the earliest ones generally showing little sign of Chinese or Korean imperial influence. Most of the art at these mounds belong to the animistic Shinto or proto-Shinto tradition.

The three sacred imperial regalia -- the mirror, sword and curved jade jewel (magatama) -- all date back to the Yayoi or Jomon periods. Authentic magatama jewels have been found at Jomon sites. The sword has been linked to Jomon phallic stones and the earliest bronze swords in Japan are probably of Korean origin and date back to the end of the early Yayoi period. However, ritual swords of Japanese origin appear also in the Yayoi era. Mirrors of Chinese and Korean origin date from the Middle Yayoi and probably were soon manufactured locally.

The Ise Shrine housing the sacred imperial mirror relic shows signs of Austronesian-like architecture.

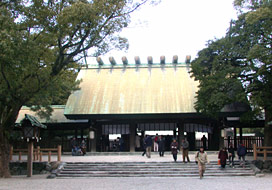

The Atsuta Shrine where the sacred imperial sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi is kept.

Yayoi culture dates at least to about 500-400 BCE, although some of the latest AMS datings suggest it could go back as far as 900 BCE. The latter date would correspond to the traditional dating of Ninigi's voyage to Kyushu, while tradition gives a date of 660 BCE for Jimmu Tenno, the first emperor.

In northern Kyushu, Yayoi burials consist of internment in large jars and stone cist graves, a practice probably derived directly from Korea, but indirectly related to Nusantao movements from further south according to Solheim.

Although there is little archaeological evidence of the existence of a state in the Yayoi period, Chinese texts tell of kingdoms in Wa, the early Chinese name for Japan, dating back to Yayoi times.

Eternal Land and Motherland

Japanese scholar Yanagita Kunio suggested that Nenokuni was a type of Japanese "Motherland" from which early Japanese migrated to Japan. The ne in Nenokuni means "root" and Yanagita has suggested that this refers to the starting-place of these early migrations. He has proposed that the same root is present in the Ryukyu word nirai as in Nirai-kanai and related terms.

Yanagita equated Nenokuni with another placename in early literature, Tokoyonokuni "Eternal Land" and both often are often portrayed as submarine or subterranean underworlds in addition as well as foreign countries. In the Nihonshoki, the word for Tokoyonokuni is rendered with the characters used for Mount Horaisan, the Japanese equivalent of China's eternal Penglai island, with the literal spelling placed in translineal kana.

Yominokuni is another name for Nenokuni, and it corresponds to the Chinese Huangquan "Yellow Springs," the underground river that rises to the surface at the foot of the Fusang Tree.

In the reign of Emperor Suinin, Tajima Mori ventures to Tokoyonokuni and upon returning in the first year of Emperor Keiko he brings back the Tachibana or mandarin orange tree. These lands are also the home of the palace of the Dragon King of the Sea who is visited by the Empress Jingo, Urashima and others according to tradition.

Marebito

The Marebito were "Sacred Visitors" connected with the festivities of the new year. They appear to preserve memories of ancient ancestors who came to the isles long ago.

In the Ryukyus and other parts of Japan, actors play the part of the Marebito visitors from across the sea. Like the ancient Kumaso, the Marebito and their equivalents in other regions were known as good dancers. Bands of singers, minstrels and dancers go from house to house during new year celebrations to bring good luck, especially for the rice harvest.

Some Japanese scholars have suggested that both the emperor and the outcaste class can be seen as descendents of the Marebito as types of "Sacred Visitors." In Japan, the actors who play the role of Marebito traditionally belong to the outcaste group.

Also, rice culture in Japan is connected with Ninigi, the imperial ancestor, who comes as a stranger from Takamagahara, and in the Ryukyus rice-growing comes with sacred visitors from Niraikanai or its equivalents.

Sacred Jars of Heavenly Mount Kagu

Mount Kagu in Yamato is said to have a heavenly equivalent in Takamagahara known as Amenokaguyama. The Nihongi states that Jimmu Tenno was instructed to take earth from Amenokaguyama to make sacred jars and dishes for a sacrifice to the gods.

Jimmu is said to have instituted the Jar Festivals including the Jar Making Festival in honor of the fire, water, mountain, firewood, moor and of course jar deities.

It is tempting to link the valued Rusun jars of the tea ceremonies of both the emperor and shogun, with the sacred jars made from Amenokaguyama earth/clay in Takamagahara to the south of Japan across the sea. Like many early Japanese pots, the Rusun jars were decorated only with cord markings -- the Nawasudare (cord curtain) and Yokonawa (cross cord).

Like early Yayoi jars, the Rusun wares were unglazed, coarse and of a "rusty iron" color.

Rusun jars were also used for yearly festivals and as imports from across the sea they fulfilled the aspect of the "Sacred Visitor."

Regards,

Paul Kekai Manansala

Sacramento

References

Blacker, Carmen. The Catalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan, Routledge, 1999.

Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko. Culture in Contemporary Japan: an anthropological view, Cambridge University Press, 1984, p. 44.

Tsunoda, Ryu-saku , Donald Keene, Wm. Theodore de Bary, William Theodore De Bary. Sources of Japanese Tradition, Columbia University Press, 1964.

0 comments:

Post a Comment