The dispersion of Lungshanoid culture, where ever it originates, is one signature of the resulting activity in the region.

Hoabinhian background

Understanding the Neolithic situation in Southeast Asia starts with the Mesolithic Hoabinhian culture and also takes into account Wilhelm Solheim's latest theories on the Nusantao.

Solheim now proposes that "Pre-Austronesian" culture begins in the Bismarck Islands off northwestern Papua New Guinea beginning around 13,000 to 10,000 BP. He cites specifically the appearance of arboriculture and shell artifacts at this time.

He proposes that by at least 10,000 BP interaction networks had been established from the Bismarcks to Indochina and South China. Here they came into contact with Hoabinhian culture. Previously, Solheim has suggested that tool edge-grinding in northern Australia radiocarbon dated to about 20,000 BCE was of Hoabinhian provenance.

Carl Sauer and Solheim have suggested that simple agriculture may have begun as early as 15,000 BCE or even 20,000 BCE in mainland Southeast Asia based on Hoabinhian finds. Although the oldest radiocarbon dates for plant remains go back only to 9700 BCE, other evidence is found in successively deeper layers with no radiometric dating. Solheim has suggested a time scenario based on the depth of these layers.

Hoabinhian culture utilized chipped pebble tools, a "pebble" referring to a gravel stone of certain diameter. They appear to have used a simple hoe, one of the oldest known farming artifacts, consisting of a transversly-hafted adze, and to have made cord-marked pottery.

The cords used by the Hoabinhian and the roughly contemporary Jomon to the north provide some of the earliest evidence of hand-spinning in the world. We also find evidence of mat-making from mat impressions in the pottery.

Some early long-range dispersions of the Pre- or Proto-Austronesians appear to have been caused by sea flooding in Southeast Asia, and these could account, for example, in cultural changes seen at places like Spirit Cave in 6600 BCE.

Shell culture

In the region of the Philippines and eastern Indonesia, a culture based on shell tools and shellfish gathering emerged sometime around 7000 BCE.

Wilfredo Ronquillo has documented some early phases of this shell mound culture including stone-flaking and shell-working at Balobok Rockshelter in the southern Philippines starting in the period 6810-6050 BCE. By 5340 BCE, we see shell and stone tools, together with some polished tools and earthenware pottery (still not classified).

A Tridacna shell adze from Palau. Source: http://www.pacificworlds.com/palau/sea/reef.cfm

The Southeast Asian and coastal East Asian tradition of polished tools is different from that of areas of inner and northern eastern Asia. In the southern areas, they continued to chip pebbles, only grinding and polishing to finish the product. This practice often continued well into the Neolithic unlike other areas where grinding and pecking displaced the chipping process.

The Insular Southeast Asian and coastal East Asian polished tools also differed from those of mainland Southeast Asia and non-coastal East Asia in that stepped adzes of quadrangular cross-section were mostly used by the former, while the latter mostly used shouldered adzes.

Balobok culture fashioned tools from the giant clam Tridacna giga, and we find this and similiar shell artifacts moving northward during the sixth millennium BCE. Shell tools pop up in Dapenkeng culture in Taiwan and in the Neolithic cultures around Hong Kong around 5000 BCE. It appears that the early shell-working in the Bismarcks was significantly enhanced in the region of the Philippines and eastern Indonesia and then taken northward by the Nusantao.

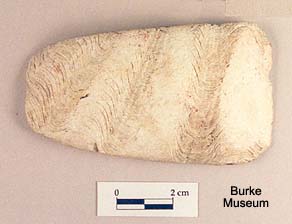

The stone and shell tool tradition in this area may be related to the earlier edge-grinding tradition in northern Australia. Most of the tools during this early period were still only edge-ground although some others like the rectangular stepped adze, found also at Dapenkeng and in the Hong Kong Neolithic sites, were more fully-polished.

At about his time we also see the appearance of the semilunar stone or shell reaping knife. It is difficult to say where this came from, but it eventually gets strongly associated with rice agriculture and becomes an important marker of Lungshanoid culture.

North-South interaction

After 5000 BCE, trade networks extending as far north as Shandong appear established. A two-way diffusion of culture begins to take place.

The Nusantao cultural kit by this time included items like the stepped adze/axe of rectangular cross-section, the semilunar reaping knife, the spindle whorl probably borrowed from the north, clay/stone net sinkers, perforated discs that may have been indigenous spindle whorls and/or net sinkers, shell tools and beads.

The image shows the process of reducing stone into the semilunar knive of the Korean Neolithic. Source: Pusan National University Museum, http://pnu-museum.org

Lungshanoid culture develops with the appearance of rice agriculture and is marked by the mainland tripod and ringfoot pottery tradition, the semilunar knives and the stepped adze. Otherwise the Lungshanoid is typically Nusantao especially in the southern locations of Fujian and Taiwan.

R. Ferrell believes the Yuanshan culture of Taiwan was "Proto-Lungshanoid" while KC Chang thought the culture may have originated in China. Whatever the case, there was a lot of exchange going on.

We also know that the Taiwanese Neolithic cultures were closely related with those in the Philippines. The red-slipped Philippine wares were very closely associated along with other artifacts to the Yuanshan wares and culture. Even the Dapenkeng sees it closest correspondence with Philippine sites. A comparison of the pottery at Balobok with that of Dapenkeng could be very revealing.

In both cases the pottery traditions are probably related to the Hoabinhian methods that filtered into the islands during the early Pre-Austronesian interactions with the Hoabinhian culture, the latter seems to be categorized by Solheim as consisting largely of Proto-Austro-Tai speakers.

Interactions between Taiwan and the Philippines continued through the Lungshanoid as rice agriculture appears to enter the islands at this time by at least 3000 BCE. Lungshanoid tripod and ringfoot pottery may also radiate into Insular Southeast Asia through the Philippines. Examples of such pottery are found at Novaliches in the Philippines and Leang Buidane in Sulawesi.

Tripod and ringfoot pottery together with the practice of jar burial also eventually moves westward into South India during the megalithic period, and apparently creeps northward into eastern India, where we hear of the practice of jar burial in Buddhist literature.

Regards,

Paul Kekai Manansala

Sacramento

References

Ronquillo, Wilfredo. "The 1992 Archaeological Reexcavation of the Balobok Rockshelter, Sanga Sanga, Tawi Tawi Province, Philippines: A Preliminary Report. With Mr. Rey A. Santiago, Mr. Shijun Asato and Mr. Kazuhiko Tanaka," Journal of Historiographical Institute, Okinawa Prefectural Library. No. 18, March, 1993. Okinawa, Japan pp. 1-40. 1993.

Solheim, Wilhelm, Archaeology and Culture in Southeast Asia: Unraveling the Nusantao, with contribution from David Bulbeck and Ambika Flavel, University of the Philippines Press, ND.

__, "Origins of the Filipinos and their languages," Paper presented at 9th Philippine Linguistics Congress (25-27 January 2006), University of the Philippines.

No comments:

Post a Comment