The art of tattoo was and is widely practiced in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Most "tribal" people here practice it to some extent.

Where tattoos are used in this region, they tend to be associated with high status and heroic deeds. This is in marked contrast to many other areas where tattoos are associated with the lower classes, or even with the criminal underworld.

Even in many areas of Southeast Asia and the Pacific, those educated in modern institutions will commonly tend to eschew such ancient practices.

Marks of distinction

Tattoos often were forbidden to men unless they had performed some heroic feat in war. In many cultures, including the Polynesian, the higher classes such as the chiefs often had rights to greater use of tattoos. The lower classes in such cases were only permitted to tattoo certain parts of the body. And specific tattoo markings commonly indicated the nobility of the wearer.

In many of these cultures, tattoos could be 'read' as they delineated various types of information about those who displayed the markings.

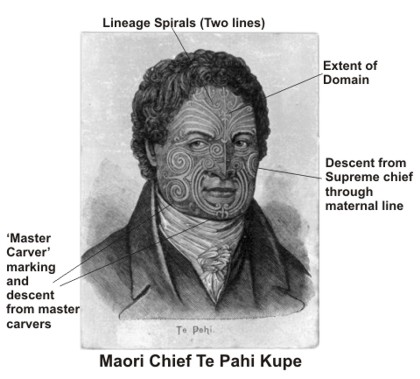

For example, the 19th century Maori chief Te Pehi Kupe had facial tattoos that indicated his descent from two paramount chiefly lines. A marking in the center of his forehead showed the geographical extent of his chiefly domain. Koru designs in front of his left ear meant that he claimed descent from a Supreme Chief, the highest ranking in Maori society.

And tattoos on the lower jaw, indicated that Te Pahi Kupe was a master builder and also claimed descent from master builders.

The Maori tattoos had bilateral symmetry or bilateral disrupted symmetry with each side of the face, for example, telling different stories.

These tattoos closely resembled the designs found on the rafters of Maori ceremonial buildings. The ridge-pole in these buildings represents the main chiefly lineage while the rafters indicate cadet lines from the main branch. These rafters are decorated with patterns known as kowhaiwhai, reminiscent of the kumara or sweet potato tendrils.

These kowhaiwhai are rare examples of Oceanic fractal art displaying aspects of recursion, scaling and symmetry.

Maori rafter and tattoo designs displaying bilateral symmetry, two-color symmetry, anti-symmetry, scaling and recursion.

The similarity between tattoo design and other artistic design used in architecture, textiles, pottery, village spatial patterns, etc. is widely found throughout the region.

Very often these designs indicate clan lineage or noble status, but at times they are used to ward off evil spirits, provide good luck or spiritual power, or simply as decorative patterns.

Most researchers specializing in this area believe that tattoo art was practiced by the Lapita peoples who entered into the Pacific. Many tattoos resemble Lapita designs or earlier geometric patterns found on Neolithic pottery further West. Tattoo needles have been found at some Lapita sites. There are many commonalities between tattoos in Southeast Asia and those found in the Pacific.

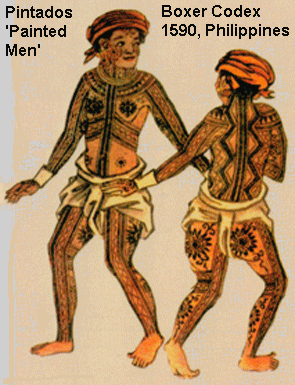

The tattoo designs are overwhelmingly geometric in character, although other imagery is not unknown. In some cases, as with the Maori and ancient Bisayans, these geometric patterns became exceptionally complex, and in most cases tattoos conveyed deeper information with reference to the tattoo wearer.

Regards,

Paul Kekai Manansala

Sacramento

References

Gardner, Helen Fred S Kleiner and Christin J Mamiya. Gardner's Art Through the Ages With Infotrac: Gardner's Art Through the Ages (with Artstudy..., Thomson Wadsworth, 2004.

Gell, Alfred. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory, Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 253.

Neich, Robert. Carved Histories: Rotorua Ngati Tarawhai Carving, Auckland University Press, 2002.

No comments:

Post a Comment